The Dr. Abigail Ross Foundation for Applied Conservation (TDARFAC)

Supporting Member of the Lemur Conservation Network

What We Do

The intention of TDARFAC is to bridge the gap between academic breakthroughs in conservation science and applied conservation efforts on the ground by generating actionable conservation interventions. Ultimately, our aim is to support novel applications of techniques and approaches from the natural and social sciences while leveraging existing knowledge to solve real-world problems.

How We Protect Lemurs and Other Wildlife

Grantmaking

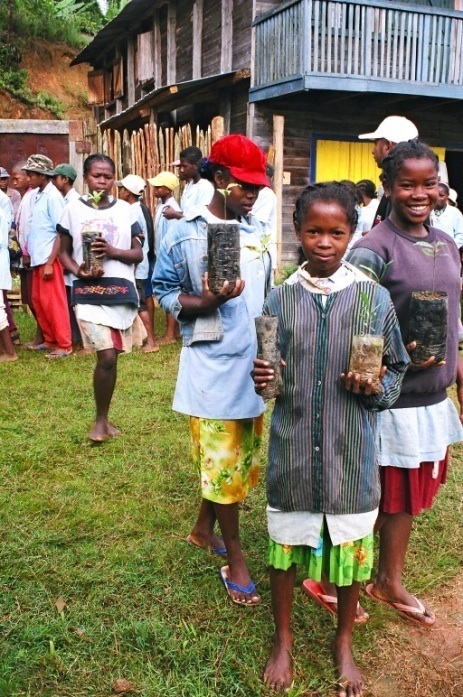

Planet Madagascar Women’s Cooperative. The cooperative engages in independent business ventures including circus farming, forest restoration, and bee-keeping in Ankarafantsika National Park.

TDARFAC provides grants to support conservation research and community-based conservation, which aligns with our mission statement and objectives:

- building capacity;

- amplifying voices; and

- partnering with local communities.

TDARFAC supports individuals, collaborations or partnerships, and non-governmental organizations working in non-human primate habitat countries. The foundation’s primary focus is assisting conservationists from low- and middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank and/or people and/or organizations working therein. However, projects based on any non-human primates, their habitats, or any animal or plant species, which share and influence the same landscapes as non-human primates and directly relate to their conservation, are eligible for funding. Grants are awarded based on the guidance and recommendations of the Advisory Council.

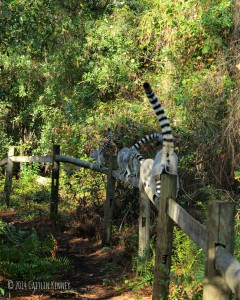

Reforestation Corridor Connecting Andasibe-Mantadia National Park and Analamazoatra Special Reserve

Reforestation corridor team collage, EcoVision Village, Andasibe Madagascar.

We are in currently in the first phase of creating a wildlife corridor connecting two of Madagascar’s most important protected areas: Andasibe-Mantadia National Park and Analamazoatra Special Reserve.

These areas are home to various Endangered and Critically Endangered wildlife species, including 12 lemur species. Wildlife populations in the two protected areas are currently not connected due to past (~1960s) deforestation that previously connected these two forests. This is a landscape scale project and hugely collaborative effort between various people and organizations.

Long-term Conservation Goals for this Project

- Replant 1,500 native tree seedlings per hectare across 233 hectares.

- Hire ten local community members to prepare land and plant native seedlings.

- Support a local native seedling nursery.

- Create a critical native forest corridor connecting some of the most Endangered wildlife populations on Earth.

- Facilitate community-based ecotourism and research projects to provide long-term employment opportunities for local community members.

What Lemur Species We Protect

Diademed sifaka in Andasibe. Photo: Lynne Venart.

Our reforestation corridor project connecting Andasibe-Mantadia National Park and Analamazoatra Special Reserve contains the following species within the landscape:

- Aye-aye, Daubentonia madagascariensis (Endangered, Population Declining)

- Black and white ruffed lemur, Varecia variegata (Critically Endangered, Population Declining)

- Brown lemur, Eulemur fulvus (Vulnerable, Population Declining)

- Diademed sifaka, Propithecus diadema (Critically Endangered, Population Declining)

- Eastern woolly lemur, Avahi laniger (Vulnerable, Population Declining)

- Goodman’s mouse lemur, Microcebus lehilahytsara (Vulnerable, Population Declining)

- Gray bamboo lemur, Hapalemur griseus (Vulnerable, Population Declining)

- Greater dwarf lemur, Cheirogaleus major (Vulnerable, Declining)

- Greater sportive lemur, Lepilemur mustilinus (Vulnerable, Population Declining)

- Hairy-eared dwarf lemur, Allocebus trichotis (Endangered, Population Declining)

- Indri, Indri indri (Critically Endangered, Population Declining)

- Red-bellied lemur, Eulemur rubriventer (Vulnerable, Population Declining)

How We Support Local Communities

University of Antananarivo – ADD students visiting our EcoVision tree nursery for the reforestation corridor project, Andasibe, Madagascar.

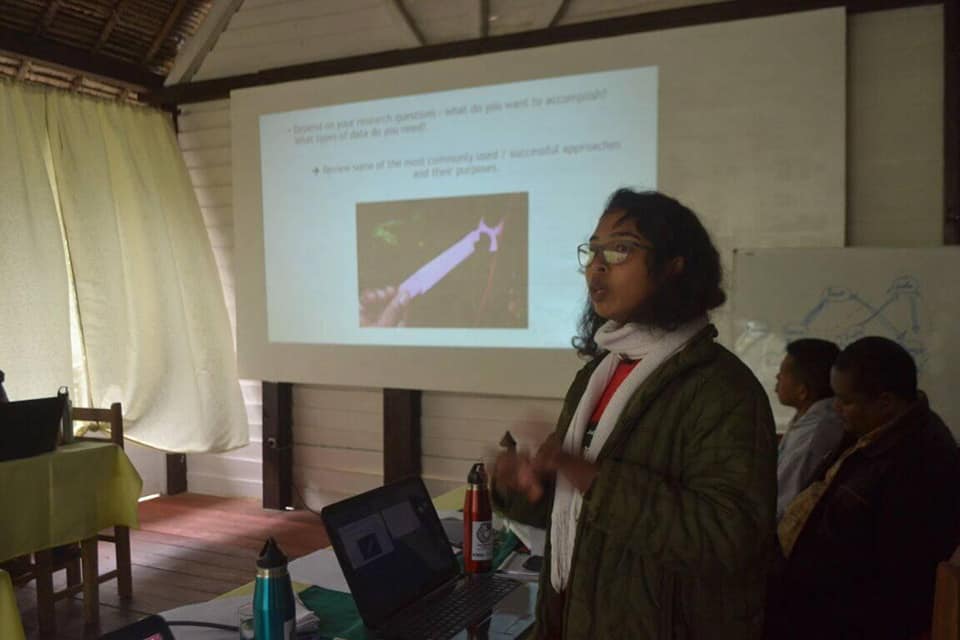

Field Training Programs for Malagasy Master’s Students in Lemur Ecology, Behavior, & Conservation

A consortium of international lemur specialists was formed in 2021 to create two parallel Field Training Programs with the intention of assisting master’s degree students at the University of Antananarivo. Our goal is to establish annual training programs at the below field sites to support the next generation of Malagasy primatologists.

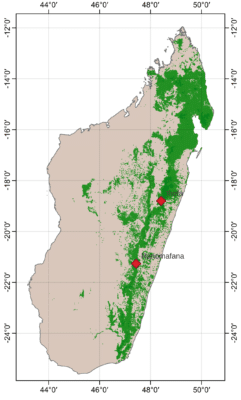

Mahatsinjo Research Station in the Tsinjoarivo Forest

Students conducted fieldwork at the Mahatsinjo Research Station within the Tsinjoarivo-Ambalaomby Protected Area, with logistics coordinated through the NGO SADABE. Tsinjoarivo forest is a mid-altitude eastern rainforest with ten lemur species. The landscape at Tsinjoarivo covers an east-to-west gradient from degraded fragments with an incomplete lemur community to intact, relatively undisturbed forest with all lemurs present.

University of Antananarivo – ADD students visiting reforestation corridor project for World Lemur Day with partners EcoVision, Mad Dog Initiative, & Association Mitsinjo.

Ampijoroa Field Station in Ankarafantsika National Park

Students also conducted fieldwork at the Ampijoroa Field Station within Ankarafantsika National Park (ANP), with logistics coordinated through the NGO Planet Madagascar. ANP is a dry deciduous forest ecosystem containing eight lemur species, and also contains networks of forest fragments in which lemurs can be studied.

Awards Program

We honor scientists and activists for exceptional contributions to the field of conservation and preservation of biodiversity. Individuals may be nominated for awards by peers, mentors, and/or colleagues.

- The Devoted to Discovery: Women Scientist Conservation Award recognizes the extraordinary and cutting-edge scientific work of women in conservation science. Women in science are encouraged to seek nominations.

- The Advocates for Change: Future Conservationist & Activist Award honours the remarkable achievements of early-career conversationists and activists in applied conservation.

Students, educators, experts, and community activists are encouraged to seek nominations.

World Lemur Day booth in Maromizaha, Madagascar.

Lemur Conservation Foundation

Lemur Conservation Foundation