Wildlife Madagascar

Supporting Member of the Lemur Conservation Network

What We Do

Wildlife Madagascar is committed to safeguarding biodiversity through habitat protection via management, patrolling and monitoring; developing local sustainable livelihood opportunities and improving food security; and developing ecotourism capacity. Only by bringing local knowledge, practicality, and priorities together with a focused scientific and educational effort will we be successful in protecting Madagascar’s breath-taking biodiversity.

How We Protect Lemurs and Other Wildlife

Indri. Photo: Lytah Razafimahefa.

Forest habitats and wildlife can only be effectively protected if the pressures of human encroachment can be alleviated. We use an integrated conservation and human-development approach to reduce pressure on Madagascar’s globally important forests and wildlife populations. We protect the habitat and provide surrounding communities with sustainable livelihoods and services.

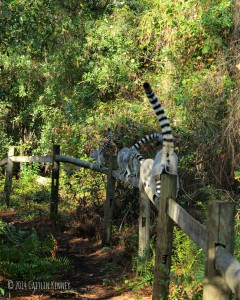

Patrolling and Monitoring the Forest

We provide protection of forest habitats through patrolling and monitoring, training, and border demarcation and enforcement.

Strengthening Communities

While habitat protection is key, working with local communities is integral to success. We aim to increase food security and income generation for local farmers through participatory, sustainable agricultural development and researching the most effective crops and livestock. We aim to strengthen the capacity of local community-based organizations and farmer leaders to facilitate community-based learning for agriculture and livelihood development. We seek to develop alternative livelihoods for community members through ecotourism and other initiatives. We provide support and supplementary education to ensure that children attend and complete primary school and become participants in appreciating and protecting their native wildlife.

What Lemur Species We Protect

Northern Bamboo Lemur. Photo: Lytah Razafimahefa.

The programs implemented by Wildlife Madagascar help protect the following species:

- Indri (Indri indri)

- Silky sifaka (Propithecus candidus)

- White-fronted brown lemur (Eulemur albifrons)

- Red-bellied lemur (Eulemur rubriventer)

- Northern bamboo lemur (Hapalemur occidentalis)

- Eastern woolly lemur (Avahi laniger)

- Seal’s sportive lemur (Lepilemur seali)

- Goodman’s mouse lemur (Microcebus lehilahytsara)

- Greater dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus major)

- Hairy-eared dwarf lemur (Allocebus trichotis)

- Masoala fork-marked lemur (Phaner furcifer)

- Aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis)

More Animals that Benefit from Our Work

- Fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox)

- Malagasy civet (Fossa fossana)

- Broad-striped mongoose (Galidictis fasciata)

- Helmet vanga (Euryceros prevostii)

- Mossy leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus sikorae)

How We Support Local Communities

Wildlife Madagascar’s programs target areas adjacent to forest where local communities currently rely on income from logging, poaching, farming, and other extractive practices. Improving farming methods to achieve greater food security will reduce reliance upon forest exploitation and encourage use of alternative food sources. Through experimental learning and action methods, the initial aim of Wildlife Madagascar is to increase yields by exploring sustainable agriculture techniques.

Lemur Conservation Foundation

Lemur Conservation Foundation